The way I see it, life is an exercise in losing. You go around leaving pieces of yourself behind, things you have lost while moving places, while leaving relationships, while changing jobs, fragments you will never recover because going back is impossible. It is my fundamental belief that a person is made of the pieces they have as much as from the pieces they have lost, that you can very well find the contour of the person I am by tracing the spaces left behind by all of the things that I have lost: a home, a country, a man I loved, the ability to trust with childlike carefreeness, the ability to rely on a functioning world instead of scurrying and stockpiling like a child of war.

I also believe that getting lost is, in itself, a way of losing: of losing the ties that chain you to your sense of self in ways that are external, artificial, sometimes even arbitrary. In my favorite book of all times, Rebecca Solnit’s “A field guide to getting lost”, she quotes Virginia Woolf on the dissolution of identity that takes place when one is traveling. Solnit says:

“For Woolf, getting lost was not a matter of geography so much as identity, a passionate desire, even an urgent need, to become no one and anyone, to shake off the shackles that remind you who you are, who others think you are”.

Both the feeling and the concept are something that has always mesmerized me: being at an airport, or in a far away city, where nobody knows who you are and thus cannot hold you to the idea that others have about who you should be, even to the idea that you yourself have about it. The disappearance of those constraints, of those markers and references, and how one can lose things temporarily -such as identity- only to recover them when coming back. But who are we in that slice of time? What is left after we lose every external reference, after we “shake off the shackles”?

Before pandemic times, I used to travel a lot for work, maybe four or five times a year. I loved traveling, even though -or precisely because- the way I traveled was all about airports, hotels and conference rooms. These, to me, are all nonplaces, in the sense coined by Marc Augé: “anthropological spaces of transience where human beings remain anonymous, and that do not hold enough significance to be regarded as “places” in their anthropological definition”. Maybe in those conference rooms I would meet my friends and colleagues, go up on stage, say some things that I might consider somewhat interesting, but right after the conference was over, that room would lose all sense of meaning to me. As for hotel rooms and airports, they are the perfect places for someone like me, always looking for the dissolution of identity, for the disidentification of my own consciousness.

This is probably a good place in this text to introduce a caveat: I live with bipolar disorder type II, dominated by periods of depression over periods of mania. For many people like me, the notion of dissolving one’s own conscience is tempting because it might mean the end of suffering. For some, experimenting with drugs might make sense, while for others, Buddhism might offer some answers, but that’s not the direction I’m going with this. Solnit also speaks about the desire for what Buddhists call “unbeing”, and says “it’s not about being lost but about trying to lose yourself”.

The desire to lose yourself might be so strong that it leads you -in the words of Solnit- “to walk into a river with pockets full of rocks”.

A few months ago, my partner of seventeen years decided to leave me. There is no need to go into further detail about that; it was one of those situations where there’s really nobody to blame. However, and even though I have a very strong personality -some might even say too strong-, his absence after almost two decades caused a sort of dissolution of identity that was hard to reckon with. What are things that I really like and what are things that I have become used to after being with someone else for so long? What are things that I like, but I have left aside to make more space for this other person? What about the decisions I made because we were a couple, like moving to a specific country or city? Do I still want those things?

It has been hard to disentangle the parts of such a long relationship that were, nevertheless, mine to keep. Similar to separating property after a divorce, there are entire vastnesses of life, spaces, logics, habits, routines, that you need to look in the face and interpellate: are you mine? were you ever mine?

Last Friday I visited a sensory deprivation tank. This is a place where you get into what seems like a very big bathtub, filled with water that contains an amount of Epsom salt that allows it to create a gravity of around 1.24, which allows the person to float effortlessly, in a pitch black, soundproof environment. To make it short, you’re supposed to not perceive any external stimuli through any sense while being in there. As I said to my therapist, whom I consulted beforehand, this seemed to me the closest experience to non-existence I could ever go through in a safe manner. And it was it, but it also was not it at all, because the core of what is you keeps existing, in the same way there’s only so much that an airport or a hotel can dissolve of your identity.

When we leave, we may think we’re taking everything with us, leaving nothing behind. But we can never take the space we leave where we used to be, the space where we are no longer. I just spent a ton of money remodeling my rented apartment and now I’m thinking of moving away because my ex-boyfriend’s absence is strewn all over the place and I cannot pick it up the way I pick up the dirty glasses I leave behind.

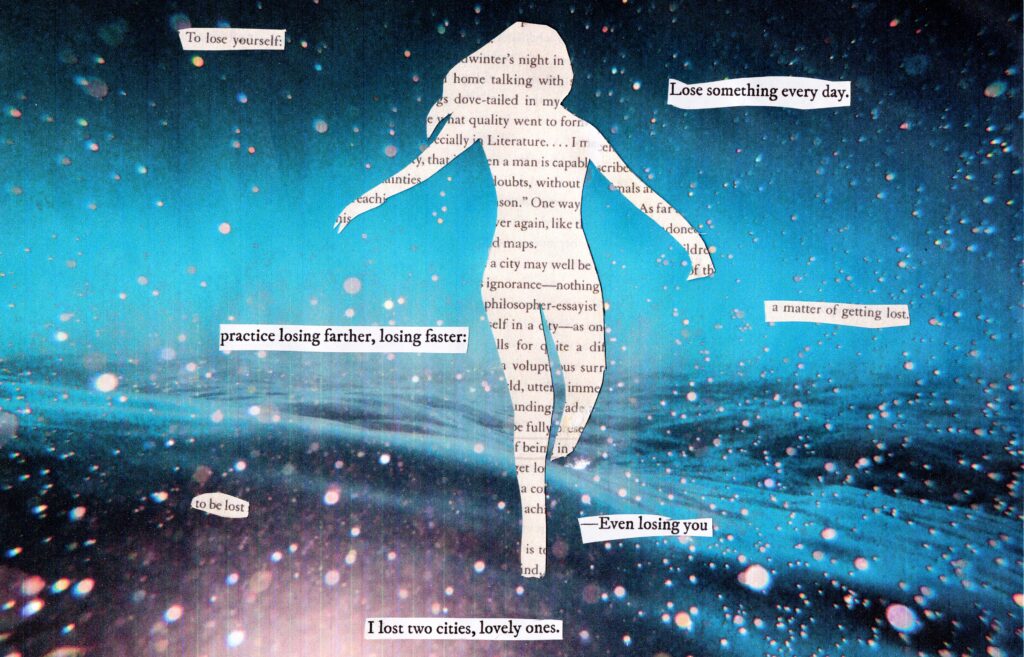

Eventually, we end up learning that there are things that have a vocation for being lost; things that are in our lives only meaning to disappear eventually. As Elizabeth Bishop says, in her marvelous poem “One Art”,

Lose something every day. Accept the fluster of lost door keys, the hour badly spent. The art of losing isn’t hard to master. Then practice losing farther, losing faster: places, and names, and where it was you meant to travel. None of these will bring disaster.

The practice of losing, I believe, is not only an exercise in adulthood but an exercise in mortality. One day we will have lost everything and everyone will have lost us, and inevitably, we will have left our absence strewn about, unpickable. As an immigrant, I also believe that migration is the mastering of the art of losing and getting lost. Flavors, accents, sounds, books, friends, we eventually learn the transience of it all, we eventually accept that nothing is ever in our lives for good.

I lost two cities, lovely ones. And, vaster, some realms I owned, two rivers, a continent. I miss them, but it wasn’t a disaster.

When moving to Chile originally, I got asked a lot if Chile was my “forever place”. This is a concept I didn’t grasp back then and now I grasp it even less, if possible. Nothing is forever, there’s only for now. Right this second, as I write these lines, there’s nothing else I can assert with such clarity and certainty as this.

—Even losing you (the joking voice, a gesture I love) I shan’t have lied. It’s evident the art of losing’s not too hard to master though it may look like (Write it!) like disaster.

Marianne Díaz Hernández (Altagracia de Orituco, Venezuela, 1985). Lawyer, writer and researcher in the intersection between human rights and technology. She has published: Cuentos en el espejo (Monte Ávila Editores, Caracas, 2008, winner of the Contest for Unpublished Authors of Monte Ávila Editores, Narrative), Aviones de papel (Monte Ávila Editores, Caracas, 2011) and Historias de mujeres perversas (El perro y la rana, Caracas, 2013, winner of the I Gustavo Pereira National Biennial of Literature, 2009), and has also been part of the compilations Antología sin fin (Escuela Literaria del Sur, 2013), Voices from the Venezuelan City (Palabras errantes, 2013) , and Nuevo País de las Letras (Banesco, Caracas, 2016). She co-founded the small press Casajena Editoras. Pieces of her work have been translated into English, French and Slovenian. She currently resides in Santiago de Chile.